Breaking the tyranny of distance

[Cross-posted at Airminded.]

Australia is a long way from anywhere, even from itself. It nearly always takes a long time to get to where you want to go. Historian Geoffrey Blainey famously popularised the idea that this remoteness has shaped Australian history and culture in the title of his 1966 book, The Tyranny of Distance. The longing of European Australians, especially, for closer connections to Europe and America found an expression in an interest in technological solutions, as in a speech given by J. L. Rentoul in 1918:

We are now living in a day when fast ocean greyhounds have broken the tyranny of distance; when the wireless has annihilated space.

A couple of years later, Rentoul might have mentioned the aeroplane: the first flight from England to Australia was completed by Keith and Ross Smith in their Vickers Vimy in December 1919. They took 28 days in total, which admittedly may not seem impressive to Australians today, when we can get to London in under 24 hours. But when compared with 45 days by steamship (Rentoul’s ‘fast ocean greyhounds’), that was a huge leap forward. And it was only the start. In the 1920s and 1930s, the England-Australia route became the ultimate venture for pioneers who wanted to test themselves and their machines against one of the longest air routes in the world: Alan Cobham, Bert Hinkler, Amy Johnson. In 1938, you could board a Qantas airliner in Sydney and be in England 10 days later; another fifteen years on, that was down to 3.5 days. The introduction of jets in 1965 brought the travel time down even further.

The interest which Australians took in these flights to and from England can be seen in Trove Newspapers. There are a lot of articles like this one, from 1937:

LONDON-SYDNEY, SEVEN DAYS.

LONDON, Thursday.

When the tri-weekly air mail service from England to Australia commences in January, 1938, it is proposed to work to a ten-day schedule, and by progressive night flying to reduce the time of the journey from London to Sydney to seven days.

As part of the Heritage of the Air project, I wondered if it might be possible to pull out these articles, and more importantly, these times, from Trove in a more or less automated way, to help visualise how Australians thought that aviation was breaking the tyranny of distance. With the help of Tim Sherratt — who did all the hard work of adapting his Trove newspaper harvester — it turns out that it is.

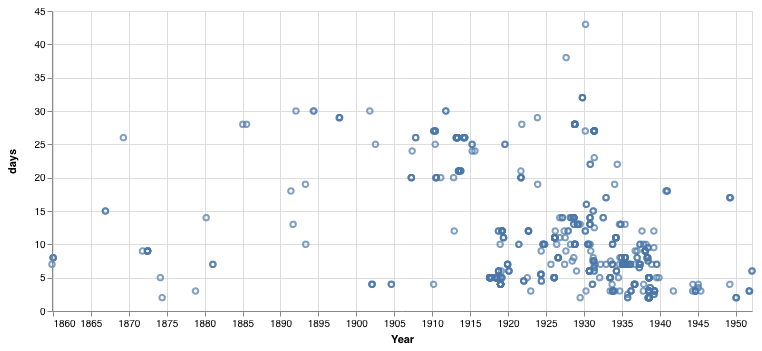

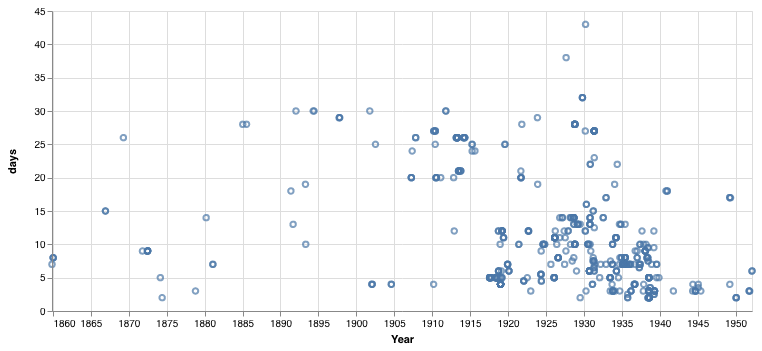

Each of the little circles in the above graph represents one newspaper article which has a headline which includes all of the words ‘london’, ‘sydney’, and ‘days’ (darker where several circles overlap). Along the bottom is the date of the article; it only goes up to the mid-1950s because that’s where Trove’s newspaper coverage effectively ends. Up the side is a number, which is (usually) a number of days mentioned in the headline. Only numbers in front of the word ‘days’ are counted (which misses ‘a day’ or ‘1 day’). Numbers written out as words have been turned into their numerical equivalents, so in the above example ‘seven days’ becomes ‘7’. Some attempt has been made to capture halves, so ‘three days and a half’ becomes ‘3.5’ (but not anything more complicated, so ‘2 days and 23 hours’ becomes ‘2’ and ‘less than 3 days’ becomes ‘3’). This is all very preliminary, and very messy.

So what does it all mean? Because the search only looks at headlines, not the articles themselves, it tends to pick up stories in which the search terms were, in effect, the point, that is ones about record-breaking flights or faster airline routes. So it favours novelty over routine. It doesn’t only pick up on things like this — as I’ll explain — but I think, to a first approximation, it mostly does show us something about how people were imagining the changing travel times between London and Sydney, both the way it was actually changing for pioneers and then airlines, and also the way it might change in the future. That thick cluster of data points in the 1920s and 1930s suggests that aviation was already shrinking the way that Australians were thinking about international distances: the world was now only days across, not weeks.

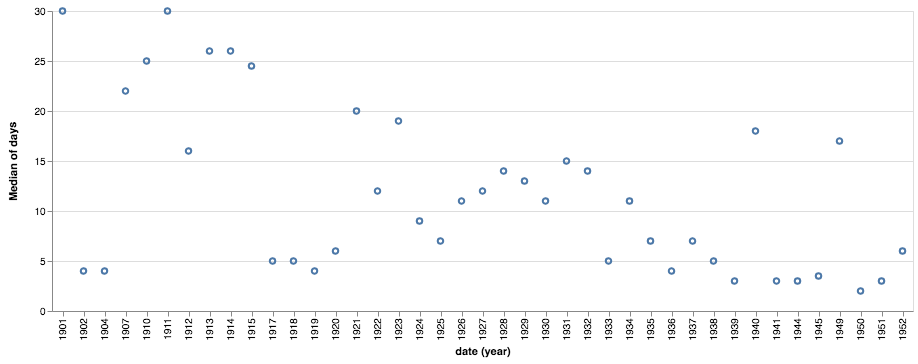

Here is the same search, but now starting in 1901 and displaying the median number of days for all the articles in each year — that is, half the numbers in the headlines for that year are above this value, half are below. It shows a clear trend from 20 or so days at the start of the 1920s, down to between 10 and 15 days in the late 1920s, down to 5 or less days by the late 1930s. But it also shows some oddities: in 1919 and 1920, for example, the time is around 5 days; in 1940, it’s up at 18. In the former cases the low numbers appear to be due to a rash of speculation about future air travel (a bit worryingly, the Vimy’s actual flight in 1919 doesn’t seem to have been picked up by our search at all). In the latter case it’s because BOAC was forced to fly a longer route across Africa, to Singapore, to avoid the Mediterranean (and Italy). The first graph suggests that after this there was a distinct lack of headlines about flights between London and Sydney, present or prospective, until late in the war.

One interesting thing about this search is that it actually has nothing inherently to do with flying. There are two place names and a unit of time; there is nothing in there about aeroplanes or airlines or flights to bias the results. It just so happens that most of the results do in fact turn out to be about aviation. While this lack of specificity does mean that some of the times plotted on this graph have nothing to do with aircraft at all, especially those before 1919 (though, surprisingly, even in the 19th century there was some press speculation about antipodean air routes), the proportion is surprisingly low. I would have expected more headlines talking about ship sailing times, particularly after the introduction of steam. Even varying the search parameters (e.g. Liverpool instead of London, Melbourne instead of Sydney) doesn’t seem to make much difference. Either this particular method doesn’t work for ships or else the press fascination with speed was more of a 20th century phenomenon.

There are other problems with the data. There will be many relevant articles which we miss, because they don’t happen to have the right words in the headlines. Also, some of the ones we do find, of course, don’t have anything to do with travelling between London and Sydney at all, but just happen to match the search criteria; for example, ‘SYDNEY SWIMMER’S SUCCESS. THREE VICTORIES IN A DAY‘. Others may have to do with flights but the number in the headline doesn’t refer to the total length of the flight; for example, when the Southern Cross was said to be ‘TWO DAYS AHEAD OF SCHEDULE‘. Or Sydney and London aren’t in the headline as endpoints, but for some other reason, such as datelines. Results like these muddy the results, but whether it is worth trying to exclude false positives like that in any systematic way is another question. For our purposes, the overall picture is more important than the fine details, and as long as the search turns up hundreds of articles, rather than just a few tens, it seems to be enough for meaningful results. So some of these things will be worth fixing, others won’t matter too much.

This is all a work in progress, so we’ll be refining it in the future. There are other things we can do with this method: looking at travel times of hours, rather than days (jets!); Melbourne or Darwin, rather than Sydney; Perth, rather than London (transcontinental rather than intercontinental). Watch this (air)space!

Pingback: Breaking the tyranny of distance – Airminded