Still here, available for rescue

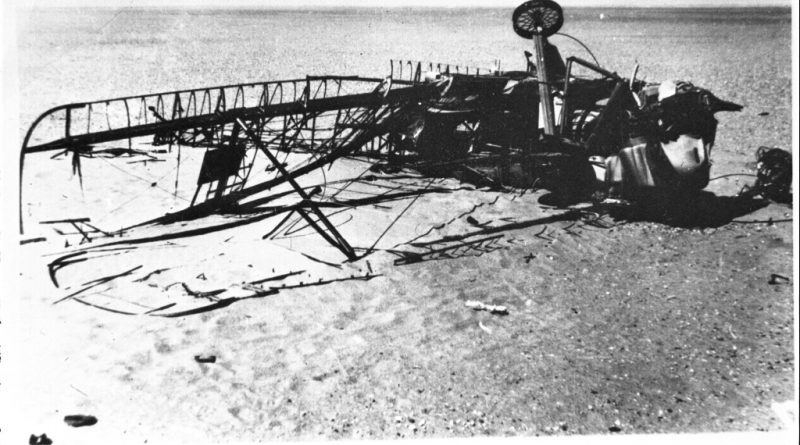

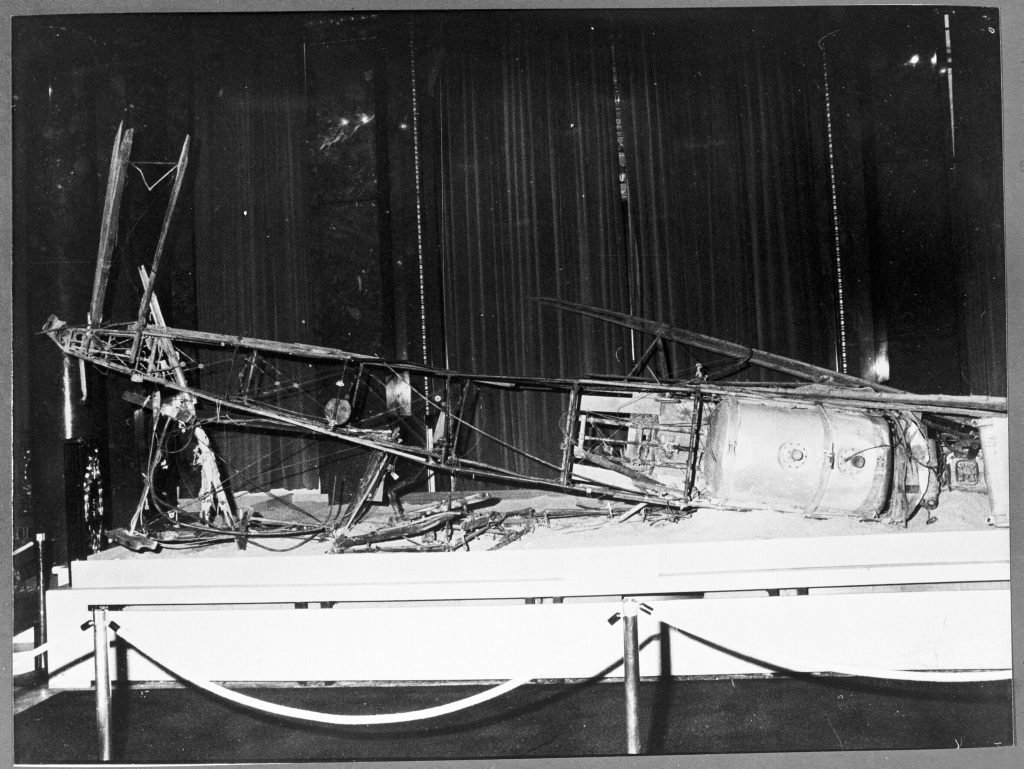

Feature image (above): ‘Wreck of the Southern Cross Minor discovered in 1962. Image courtesy of the Thomas Macleod Queensland Aviation Collection, Queensland Museum.’

I was recently lucky enough to participate with Tracy Ireland in the annual Theoretical Archaeology Group USA conference (TAG) in Syracuse, NY. The theme of the conference was ‘slow archaeology’ and involved, among other things, a renewed focus on empirical research, the importance (and power) of the material and embodied, and emerging perspectives that may contribute to an academic environment that places less of a premium on ‘fast’, cerebral, anthropocentric work.

My own focus lately has been on that body of theory known as new materialism, and on object biographies in particular, and we decided this would be an ideal approach for TAG. Reading Tracy’s recent work allowed me to gain an understanding of the concept that then became the groundwork for my subsequent research. Object biographies concern themselves with what things do, rather than what they mean, and thus can offer insights into the human and more-than-human entanglements in which a thing is embedded throughout its lifetime. These entanglements are necessarily embodied and experiential, and an object biography perspective constitutes a reframing of object-person relationships to allow for ‘thing agency’, or the power of things to exert their own influence, independent of human will. It is also a method that focuses on affect – used to denote the precognitive, embodied, sensual and emotional relationships between bodies, living and non-living. In other words, a new materiality framework aims to decentralise the human point of view and recontextualise it in a greater network of people and things.

This was our claim to slow methods. For our paper, we chose a case study that has occupied a great deal of our time lately – the wreck of the Southern Cross Minor. The history of this plane is quite remarkable, spanning Charles Kingsford Smith, the possible murder of an American journalist, the London to Cape Town aviation speed record, a fatal crash and the French Foreign Legion, to name just a few elements! In fact, the story is so fantastic that I found it – and still do find it – rather difficult to put that complex human, historical lens to one side and concentrate on what the object does. The human focus insists on its own primacy. To be fair, it is important to know what has been done to the wreck in order to think about what it has done. It is important to know, for example, that the plane crashed in the Sahara in 1933, that the pilot, Englishman Bill Lancaster, died at the scene eight days later, and that the plane remained in the desert until 1975. It is important to know that in 1962, a French Foreign Legion patrol found the wreck and removed Lancaster’s remains, leaving the plane where it was. It is important to know that the eventual expedition to recover the Minor and bring it back to the Queensland Museum was driven by the passion/obsession of the museum’s librarian Ted Wixtead, who built the story up in his mind to be another heroic tale of pioneering Australian aviation. It is even important to know that before Lancaster bought the plane, it belonged to Australian aviator Charles Kingsford Smith, and that a great deal of the mythos surrounding the wreck stems from this association – despite the fact that he owned it for less than two years and may never have completed a single successful flight in it. All of these things contribute to the multifaceted interpretation of the wreck as a complex object. They simply do not constitute an object biography.

What, then, does the Southern Cross Minor do?

For me, the breakthrough occurred when I began to read about the ruin archaeology of old military sites and the archaeology of coastal drift matter – vast assemblages of junk that wash up with the tides and accumulate. These emerging bodies of work are both concerned with material that is not what it might be, damaged, decaying or unwanted. It ‘ruins’ beaches, it drags communities backwards into the past, it presents uncomfortable and insistent reminders of global environmental change and the role we have played in bringing it about, it raises unanswerable questions about the future of the planet. The attention it draws – especially drift matter collections – tends to focus on disassembly; getting rid of it and thus ‘fixing’ some problem of which it is symptomatic. What authors such as Caitlin DeSilvey, Þora Pétursdóttir, Bjørnar Olsen and others posit, however, is that there is no getting rid of these ruins. Regardless of how we feel about the situation, their continued existence is a fact we cannot escape, and a more productive approach might be to consider how we could live alongside them, how we might reframe ourselves as inhabitants of a ruined world.

Of course, there are some key differences between the Minor and the garbage heaps. The Minor has been actively conserved, it has been sought after and valued, moved about, built and rebuilt. Comparisons between the wreck and a pile of rubbish would draw outrage from several quarters. However, for all that, there are similarities that I believe it is important to recognise. The Minor, too, is a ruin. It also inspires thoughts of its ‘better’ past, and its decay is what now draws us to pay attention.

What does the Minor do? It persists. Like the garbage heaps or the abandoned military bases, it continues to exist in direct defiance of circumstance. The desert whittled it away for twenty-nine years in isolation, and it persisted. The Legion patrol declared it worthless and consigned it to another thirteen years, and it persisted. The stories that developed around it concern heroism, courage, patriotism – as tenuous as these claims may be for an Australian plane that belonged to an English national who flew once under a cloud of ill repute and died – but they are grounded in the mere fact that the Minor is still here, available for rescue and acclaim. Stripped of its own mobility, it causes us to move instead, drawn by nothing more than its presence in the world – like a weight on taut fabric that we roll towards. That is the affect of the Minor, and the principal concern of my object biography.

As always, I have to pull back and ask myself what this means for the greater network of aviation heritage entanglements we are uncovering. What are the implications of ruin heritage, or slow methods, for the relationships between people and planes? What perspectives might a new materialist framework bring to light? As I peer further down into the Minor’s biography, how many other distorted shapes of the world will I see refracted back at me?